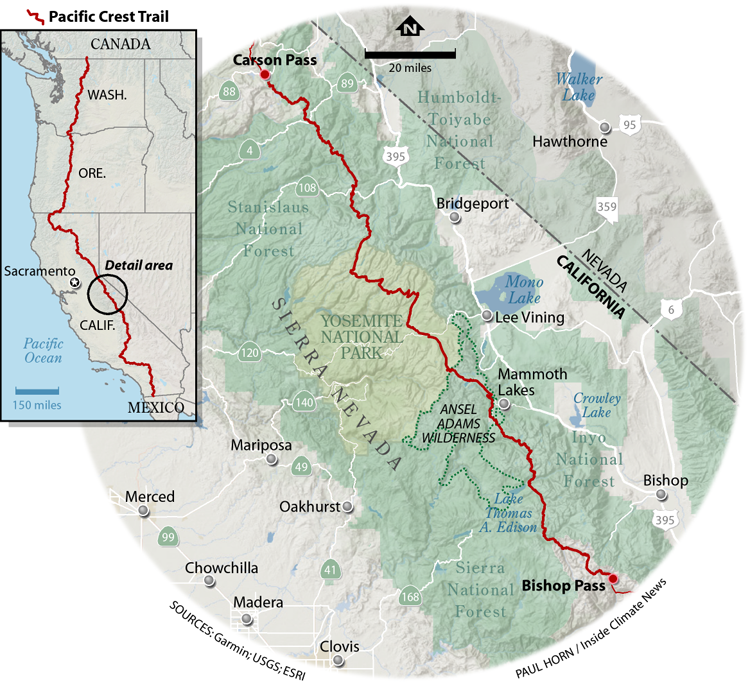

Miles to Go: The third in an ongoing series Inside Climate News fellow Bing Lin is reporting from the Pacific Crest Trail in Northern California. Over the course of a 500-mile-hike, the series is exploring the impacts of climate change on the trail and what outdoor recreation can teach society about sustainability, adaptation and coexistence in a warming world.

“Don’t strive to make your presence noticed, but your absence felt.”

What a perfect way to describe water, I mused of the aphorism, parched and probably delirious after hiking almost nine miles without any of it. Two back-to-back streams I’d been counting on for refills were bone dry, and just like that I found myself in quite a pickle. My navigation app for the Pacific Crest Trail listed my next reliable water source as another five miles away.

I had expected water aplenty throughout northern California, but I was still between Carson Pass and Yosemite National Park, just heading into the high Sierra Nevada where most of my hike would take place, and had already run dry. As I stumbled on, step after desiccating step, the whole world soon became about water. Where I would find it next and, oh, how much of it I would drink.

Blessedly, much less than five miles later, the trail rounded a corner and merged with a dirt road, where three Jeep 4x4s were parked, their occupants lounging nearby. I must have looked as bad as I felt, because one of them beckoned me over. “Hey bud, you need anything? Water?” I would have teared up if I had any fluids to spare.

Most long-distance hikers, no matter how well prepared, will have had a similar water story at some point in their adventures. Day to day, most of us have ready access to clean drinking water just a few steps away, so we easily forget how helpless we’d be if this weren’t the case.

Hikers on the PCT occasionally might need to carry enough water for a day or more of walking. Some stretches of the south California desert extend for up to 30 miles without reliable water sources. Often, though, it’s the unexpected waterless stretches that get you, as I learned the hard way.

For Stephen Clark, a 31-year-old thru-hiker from Annandale, Virginia, it happened on his second day hiking the PCT this year. “I only hiked 11 miles my first day and got to a point where I couldn’t keep going,” Clark remembered. He made camp with practically no water and woke up the next morning dehydrated, dazed and very desperate. Two other hikers he asked for water had none to spare.

“My pee was brown, and I’ve never been like this before,” Clark said. “When I finally got to the creek, I probably pounded three or four liters of water.”

It took him over 24 hours, languishing alone in his tent, before he recovered enough to continue hiking. “Should I call somebody?” he remembered asking himself. It was only Day 4 of his hike.

Clark and I met in the trail-famous town of Bishop, as bunkmates in The Hostel California, whose initials, THC, I soon learned, were well earned.

“Water dictates everything,” said Clark. “The same thing you depend on in the desert can kill you in the Sierras. Desert, Sierras, Oregon and Washington. Beating snowfall as you race to Canada. It’s a delicate balance.”

“Man, it might be because I’m high, but I’ve never thought about [water] like this before!” Clark added, sheepishly.

On the trail, water truly does dictate most decisions. The availability and quality of drinking water dictates how much to carry, how to purify it and how far to walk each day. Water from the weather—rain, snow, sleet, humidity—dictates when the PCT thru-hiking season begins. It usually begins between March and May so a northbound hiker hits the Sierras after the snowpack on its passes has sufficiently melted to allow for safe passage, and ends by September or October, before the snow begins to dump on Washington.

“You think about your timing in terms of snowmelt and snowfall,” Clark said of the cycle that determined whether he had water in his bottles or ice under foot. “In the Sierras, I traded a few liters for an ice ax and microspikes.”

On the trail, Clark’s and my experiences amount to what scientists call a cross-sectional dataset, a set of observations occurring over a single slice in time. Those limited observations of abnormal weather can be difficult to put into the broader context of climatic trends.

“Part of the reason it’s so hard to see climate change is that there’s so much variation from year to year that it hides the trend,” said Naomi Tague, a professor in ecohydrology and ecoinformatics at University of California, Santa Barbara.

“Everybody wants these easy prescriptions that work everywhere,” she said, but “How much water you have in a particular stream depends on the snow it got that year. It depends on geology. It depends on how big that watershed is. It depends on the type of vegetation. You want to start putting all the pieces together. That’s how you get an integrated systematic perspective.”

Given this, it’s hard to attribute any single thing I see when hiking—dry streams, raging rivers, rapid snowmelt or unexpected snowfall—to long-term climate change.

“It’s hard to see,” Tague said. “You’ll have to be walking for years.”

While I haven’t been out for long enough to detect the environmental signals from the seasonal noise, scientists over the decades have.

Climate whiplash is increasing the amplitude of weather extremes, exemplified by vacillating periods of extreme wet and dry. In California, extreme heat can come hot on the heels of flash flooding in the Central Valley. On the trail, it often seems that when fire isn’t burning everything up, water in its many forms is bogging everyone down.

Hotter temperatures are also messing with the snowpack that functions as a natural water tower that slowly melts in the spring and summer to moisten forests, fill reservoirs and irrigate crops. High elevation snowpack is especially important, but these days, more cold season precipitation is falling as rain instead of snow, running off immediately and washing away the already reduced snowpack that does accumulate. Over time, this could contribute to seasonal streams becoming even more ephemeral and longer stretches without water for desperate hikers.

“Our dams are not designed to hold the larger quantities of water that [now] fall in shorter time periods,” said Colleen Naughton, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at University of California, Merced. This premature rush of precious water downstream can be wasteful and lead to flooding and landslides. (Solutions for California’s increasingly volatile drought and flood cycles include tactics like Managed Aquifer Recharge, which can take advantage of periodic flooding to replenish the state’s subsurface groundwater.)

Importantly, Naughton also stresses that climate change is not just about warming. “The general public can perceive climate change as only warming,” Naughton said. “[But] it leads to more extremes for both hot and cold. Some years we may still set records for snowpack.”

Just last year, snowpack on the PCT broke records, growing to roughly 300 percent of what is typical, making a “true thru” hike from Mexico to Canada nearly impossible for the aspiring PCT trekking class of 2023.

When I got to Carson Pass, just south of Lake Tahoe, one of the volunteers at the visitor center pointed out a white flag on a towering conifer right outside the building. From ground level, it was a tiny speck on a branch at least 30 feet above us. “It’s at least three stories high,” said another staff member, describing how a ranger had simply walked on the snow up to the branch to tie the banner there at the height of the 2023 winter. It was a staggering thought.

Water, Water Everywhere

“From the ridges to the ocean, right?” said Letitia Grenier, director of the Water Policy Center at the Public Policy Institute of California. “These very big processes, close to and very far from the Pacific Crest Trail, actually affect the vast majority of our state.”

Grenier had just returned from a multi-day backpacking trip in the Sierras herself when I caught her on a call.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“If you think about our watersheds, they are highly managed at the bottom, but here’s a place at the top where they’re not,” she said. “And so to see them in this, you know, as-pristine-as-we’re-going-to-get-them-in-California condition, was really amazing.”

At the tip-top of California’s watersheds, in the High Sierra, water is often everywhere. It is in the roaring rivers and streams hikers cross, sometimes up to ten a day. It is often seeping from snow in rivulets directly onto the trail, resulting in a game of hiker hopscotch between rocks to keep feet dry. It fills the many alpine lakes sandwiched in mountain passes the trail crosses, each looking like a postcard.

It’s also impossible to hike through the Sierra Nevada and not appreciate how beautifully crisp, cold, clear and clean the water is. It beats the original contents of my now-battered Smartwater bottle 10 times out of 10.

I’d been hiking for close to 350 miles when I crested Donohue Pass and truly felt like I had entered the High Sierra. By then, I felt dialed in. Wake up at 5:30 a.m. and hit the trail by 6. Hike to the first water source, chug what remained in my bottle and fill up. Rinse and repeat until 8 p.m., with stops for gorp, landscape gawking and gasps of air on the scattered ascents into the alpine. Sound asleep by hiker midnight (a.k.a. 9 p.m.).

I took a day to recharge and re-supply at Mammoth Lakes, a surreal ski-resort town in Mono County that seemed to me like it was transplanted from Disneyland. I enjoyed a brilliant but bank-breaking latte at Black Velvet Coffee, snagged a women’s Patagonia down jacket for $20 at a thrift store, bought a balaclava from the locally based Ridge Merino (where PCT thru-hikers get a discount and their picture on the wall) and then shopped at the town’s crown jewel, a Grocery Outlet, where I bought a full-sized watermelon and six ice cream sandwiches to eat for dinner. Town days are the best.

On the free town trolley back to Mammoth Pass, the portal from which I’d be able to hike back onto the PCT, a young woman in a blue historic dress joined the passengers. She introduced herself as an anachronism from Mammoth Lake’s past, and proceeded to give us a historical tour of the sights we were passing. Either she was good at putting on her character or I was bad at seeing through it, but I couldn’t tell whether her incredibly thick southern drawl was put on. We learned about Dave McCoy and his singular vision to turn Mammoth Mountain into the multi-million dollar outdoor sports behemoth it is today.

“Los Angeles owns a third of Mammoth Lakes’ water,” she said, describing the City of Angels’ historic and controversial control of water rights all across the Owens Valley. “Now, does anyone know what a fish says when it hits a wall?” “Dam,” I said—I had heard that punchline before. “Damn, you stole my joke!” she said.

But I was still thinking about all the hundreds of miles the water from Mono Lake and the neighboring area has to travel to reach Los Angeles, and the other water carried to California in the Colorado River from a thousand miles away.

On the trail, I had to plan for my own water—how much water to have, where to source it and how long it’ll last. But cities, writ large, work under the same constraints. There might always seem to be potable water running from California taps, but it won’t last forever without a sustainable way of maintaining the supply that the state still has yet to find. I might be the one begging off-roaders for water, but as I’m slowly learning, my problem really seems to be to be a challenge for all of us.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,