Miles to Go: The second in an ongoing series Inside Climate News fellow Bing Lin is reporting from the Pacific Crest Trail in Northern California. Over the course of a 500-mile hike, the series is exploring the impacts of climate change on the trail and what outdoor recreation can teach society about sustainability, adaptation and coexistence in a warming world.

Hugh Safford is not your average professor. For starters, his bathroom reading includes tomes such as “Ice & Mixed Climbing: Modern Technique,” both the 2018 and 2021 issues of the American Alpine Journal and “The High Sierra: Peaks, Passes, and Trails.” For another, his counteroffer to my request for a Zoom interview was to do it instead over 50 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail together.

Safford and I initially connected through the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s SciLine service, linking journalists with scientific experts. I arrived at his driveway in Meyers, just south of Lake Tahoe, still haggard from the trail, a few days after getting to Carson Pass. “I’ll leave the front door open,” Safford had messaged. “Go ahead and get your clothes washed and take a shower and feel [free] to grab a beer from the fridge!” I gratefully made myself at home in his house and aspired to offer this level of hospitality to others in the future.

It would be fair to say that Safford knows a little something about wildfires, in addition to hiking. He was the U.S. Forest Service’s regional ecologist for California, Hawaii and the Pacific territories for 21 years, up until his retirement in 2021. At 61, he’s also still an adjunct professor at the University of California, Davis, running a lab researching vegetation and fire ecology and management; chief scientist for Vibrant Planet, a public benefit corporation focused on creating climate resilient ecosystems and communities, including wildfire mitigation; director of the Sierra Nevada section of the California Fire Science Consortium; and the principal investigator of the California Prescribed Fire Monitoring Program. Safford had a lot of duties to run from to join me on trail.

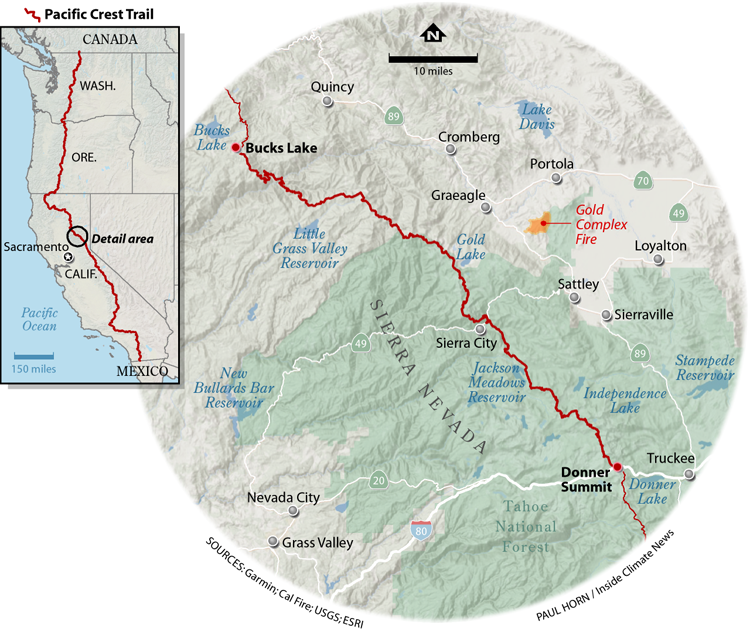

After a blissful night’s rest on a bed that put my sleeping mat to shame, Safford and I drove three hours north to Quincy to finally hike that searing-hot section of trail I had missed the week before. During our drive, which covered two weeks’ worth of my mileage on trail, I quickly picked up on Safford’s bottomless well of ecological knowledge, frenetic energy and appetite for endless edification.

“I’m pedantic as hell,” he told me later as he cited his decades in both school and higher education. Luckily for me, Safford was pedantic without being pretentious, and he possessed none of the pomposity that his 38-page CV might otherwise imply. By the time we had driven the length of Lake Tahoe, I had already learned more about fire regimes and forest ecosystems in California than in all my undergraduate ecology and evolutionary biology classes combined.

“These forests here,” Safford said, pointing through the windshield to the left, “they’re adapted to very frequent wildfires but haven’t had them for 100 years. And that’s the single biggest management issue out here. They’re way too dense, there’s way too much competition, and as a result, there’s a crazy amount of mortality. When fire hits, f—, it’s all gone,” Safford said, drawing out the letter “k” in his expletive and gesticulating wildly. In its annual aerial survey of the state’s forests, the U.S. Forest Service estimated that roughly 28.8 million trees died in 2023, just in California. The state’s office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment estimates that 237 million trees died in the state between 2010 and 2023.

“When you thin a stand, you’re reducing biomass and you’re reducing the propensity for fire to propagate through the stand,” Safford continued. “You shouldn’t use a bulldozer, go clear-cutting or rip everything up, but most of the stuff we do is selective thinning and prescribed burning. You’re basically restoring natural forest processes and patterns.”

Once we got to Quincy and hitched a ride up to the PCT at Bucks Lake with Kyle Merriam, the Plumas National Forest ecologist and one of the first employees Safford hired back in his Forest Service days, our lessons quickly continued. Safford walked me through the danger of excessive fire suppression practices in the American West and their reverberating consequences. Putting out too many fires created overly dense, fuel-rich stands across the state and the country. In a climate-worsened drought, any spark, from a lightning strike or a stray ember from a campfire, can set them off. But the vast majority of wildfires are human-caused.

“The fire threat is much lower in most of the East due principally to summer rainfall and dominance by less flammable broadleaf trees,” Safford said. “In the West, conditions are crazy, the topography complicates things, and there’s also no culture of [non-Indigenous] people using fire as a tool. So that’s a problem.”

Deficit of Good Fire Brings More Infernos

Widespread recognition of natural forest fires in California as an irreplaceable ecosystem process only took root in the late 1960s, I learned, and only after more than a century of humans suppressing natural wildfires. Harold Weaver, a forester for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, presaged the problems of wholesale fire prevention as early as 1943, when he wrote about the ponderosa pine ecosystems of the Pacific Slope, which rely on frequent fires that burn slow and low on the ground to remove competition and thin stands. “An incredibly prescient paper,” Safford said.

Then, Starker Leopold, the eldest son of the famous American writer, scientist and conservationist, Aldo Leopold, came along and helped to officially put fires back into the management toolkit. “They developed an amazing roadmap for the future of the park systems … as being microcosms, or macrocosms, of natural ecological process and not just cultivated city parks,” Safford said. “And by the way, this fire thing, it’s actually pretty important. There are species that need it, not just plants but wildlife, it’s an important recycler of nutrients… It engendered this philosophical revolution,” he said, citing the landmark Leopold Report that Starker wrote for the National Park Service.

Giant sequoias, for instance, depend on regular, low-intensity ground fires for regeneration and have evolved an arsenal of traits—thick bark, high-rising branches and seeds held in cones that are glued together unless there is sufficient heat—to not only cope with, but take advantage of a cycle of occasional fires. This helped scientists understand how important fires can be when they occur in the right dosage and timespan. Today, the severity and increased frequency of wildfires are ravaging sequoias faster than they can reproduce.

Safford had questions for me, too. “You know chaparral, right?” he asked. “You ever worked with optimization before? You know anything about trees? You know about the wildfire crisis strategy of the Forest Service?” After a few tentative yeses, I quickly learned that in fact I didn’t know anything about anything.

“Eriogonum nudum. That’s naked buckwheat,” Safford said, stopping mid-stride to show me. Rubus parviflorus is delicious thimbleberry. Lupine has beans that taste like wild edamame when sufficiently dried. The height of where wolf lichen first starts to grow on a tree marks the average snowfall that tree receives (we passed stands in which the average snowfall ran upwards of 20 feet high). Red fir needles look like verdant snowflakes when viewed from below.

After the first day, my mind felt like a thimble overflowing with wisdom gushing from a fire hydrant. In camp by Bear Creek, Safford was distracted for a few minutes by a bulbous blood blister that had formed on his heel, likely from the sharp sideways slant of the trail we’d just traversed. I took the opportunity to recuse myself and promptly passed out in my tent. I had almost made it to 8 p.m.

On our second day and most of our third day together, the trail snaked through stand after stand of snag forest—charred woods in which every tree is burnt to a crisp. Learning about fires and feeling their outcomes hit differently now. These jagged stumps of dead wood are critical habitat for species like the black-backed woodpecker. With the forest canopy burned away, the bright sun highlighted the vivid green of the vegetation regenerating in parts of the fire-thinned understory, which contrasted dramatically with the blackened trunks. It’s how I imagined Mordor would look.

“This is all the North Complex fire in 2020,” Safford said, pointing at the destruction around us, stretching up and down the hills and dotting off into the horizon. The North Complex burned over 300,000 acres, incinerated almost 2,500 structures and killed 16 people, the deadliest event in California’s 2020 fire season.

Without tree cover, nothing shielded us from searing heat. While it was markedly cooler than the week before, noontime temperatures still hovered in the low 90s. I trotted behind Safford as we clambered over and around the burnt-tree blowdowns blocking our path, feeling like we were on the interactive component of a school field trip.

Safford taught me about fire triangles. The first is the three ingredients needed to make a fire—fuel, oxygen and heat. The second is the behavior triangle, the three determinants of how a fire behaves once it’s lit—fuel, topography and weather. “In both cases, pretty much the only thing we can manage is fuel,” Safford said, citing tools such as selective thinning and prescribed burning. “Well, and weather,” added Safford. While day-to-day meteorological conditions remain outside of our control, reducing the carbon emissions that are increasing global temperatures can slow humanity’s stoking of fire weather.

With climate change, it seems like many forest management insights are fast becoming a case of too little, too late. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) reported 5,210 wildfires burning over 821,000 acres of land by August 16. Those are significantly higher numbers than the state’s five year average to that date, even with the previous five years having six of the state’s largest eight wildfires on record and some of its most destructive wildfire seasons.

What’s worse, rising temperatures are making wildfires even harder to deal with. “Fires used to sit down at night,” Safford said. Now, increasing nighttime temperatures mean that fires have 24 hours each day to rage and spread.

“If you’re speaking of climate change, hardwood forests are where it’s at,” Safford said. Broadleaf (hardwood) trees are more resilient to ecological disturbances, including wildfires, drought, beetle outbreaks and warmer temperatures, edging out conifers (softwoods) in their climate adaptability. “Conifers are toast. Fires are going to get them, beetles are going to get them.” Safford described the many bark beetle species simultaneously plaguing conifer forests in the Sierra Nevada. “White and red fir are being wiped out by a beetle called Scolytus,” said Safford. “Sugar pine is being wiped out by the mountain pine beetle. And there’s a lot of lodgepole pine dying too.”

When I asked him to show me one of the beetles, he said, “They’re as short as your small fingernail. They’re teeny little things. But there are millions of them. Billions. Trillions, probably.”

All these problems coalesce into one. “Look at all the dead trees up in here,” Safford pointed. “Dead fuels are way more flammable than live fuels.” Due to interactions between warming, drying, fire, insects and disease, Safford suspects conifers might be on their way out as dominant species in lower elevation Sierra Nevada forests in as little as 50 years.

I Learn How To Use My GPS SOS

By kismet or coincidence, the day after Safford left the trail by Gold Lake, I experienced my own personal wildfire emergency.

My day had started normally enough—I bagged 20 miles and a dip in a creek by Jackson Meadows Reservoir, all before lunch. I had eyed some suspicious thunderheads from afar and heard several successive thunderclaps in the morning, but thought little of it. Walking through a timber concession, I even attributed the thunder to the sound of falling trees, fooled by the blue skies overhead.

I continued walking in the early afternoon, and as I crested a ridge, I saw a hiker in a watermelon shirt pacing just off the trail. He beckoned me over and pointed at the horizon. Dead north of us, in the general direction I had hiked from, I saw a billowing plume of smoke rising in the distance, definitely not there the last time I had looked that way.

The hiker, Clayton Duffin, introduced himself as “Can Do” (thru-hikers customarily go by trail names on their journeys). We called into the Yuba River Ranger District to report the fire as we watched it grow. They picked up immediately, and after a few minutes, told us that they had identified the fire on their cameras and that we were the first to call it in. We were impressed by their efficiency, but daunted by their lack of further guidance. “I guess they’re just sitting around waiting for a fire, just twiddling their thumbs,” Can Do said, adding that he respects Forest Service firefighters and admires their efforts to protect woodlands.

Not knowing what to do next, I decided to stay the course south, thankfully away from the flames. In the scuttlebut passed down the trail, I learned by dinner the blaze’s name: the Mill Fire. It would soon be ensconced within the Gold Complex fire.

At dusk, I camped alone on a ridge, roughly 10 miles south of where Can Do and I had first spotted the fire. I hadn’t seen a soul for hours, and the smoke had now completely clogged the horizon. I still didn’t have cell service. Saturated with knowledge from my days with Safford, I recalled how wildfires could travel tens of miles an hour on a good draft, and thought of all the charred debris we had passed just a couple days prior.

In the fading light, I watched the smoke swirl and finally decided that I didn’t want to be someone else’s wildfire story. I couldn’t outrun a fire and figured this was the exact reason anyone would lug a Garmin satellite communicator with them for hundreds of miles. I triggered the SOS button.

Over an hour of delayed back and forth messaging with a Garmin representative that barely passed the Turing test, I desperately tried to get advice on whether I should evacuate. Finally the following text from the Plumas County Sheriff got through: “There are no fire evacuation orders or warnings in Nevada County. The nearest fire is approximately 20 miles from you in Plumas County. Your discretion.” I took a good look at the smoke, a harder look at my sleeping bag, and at my discretion, promptly fell asleep.

I woke up the next day happily unsinged, but promptly left camp. The cloud of smoke looked much less ominous in the morning, but I was grateful to have my increasingly interactive lessons with wildfires end here.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,