Miles to Go: The first in an ongoing series Inside Climate News fellow Bing Lin is reporting from the Pacific Crest Trail in Northern California. Over the course of a 500-mile hike, the series is exploring the impacts of climate change on the trail and what outdoor recreation can teach society about sustainability, adaptation and coexistence in a warming world.

SOUTH LAKE TAHOE, California—Suffering on your own terms is such a luxury. Force someone to walk thousands of miles through wilderness and it’s cruel and unusual punishment, but call their route a national scenic trail, and suddenly, thousands voluntarily subject themselves to its agonies each year and wax poetic about it.

In 2019, I was one of those suckers “thru-hiking” the Pacific Crest Trail. Iconic in the hiking world, the PCT is a 2,650-mile-long continuous dirt path that meanders from the U.S.–Mexico border to Canada along the mountain crests of California, Oregon and Washington through 51 wilderness areas, 25 national forests and six national parks along the way.

Back then, as a typically buccaneering twenty-something, I first wanted to hike the trail for the thrill of it, and then had to undertake the trek after telling too many people about my plans. Four months after setting off from the southern terminus in Campo, California, after rambling through sand, snow, smog and sleet, I made it to the northern end in Manning Park, Canada, completely in tears. Tears of delight in having hot water and a hotel room after two thousand miles of walking, but also of frustration for having skipped an entire 500-mile section of trail due to record late snowfall throughout the Sierra Nevada mountain range that year.

Mine was far from the only thru-hiking failure in that or any year. But increasingly, it’s the effects of climate change that are breaking hikers’ strides. Volatile wildfires, the key culprit, have been increasingly dashing the dreams of many others through trail alerts and closures, but the list of weird and wacky hazards befalling the trail grows by the season. Heatwaves. Wildlife attacks. Deaths under a rotten, falling tree and in a raging river crossing. Walking thousands of miles through nature exposes how fickle it can be, and climate is raising the stakes.

Five years after my interrupted trek, I’m back to finish what I started: that pesky 500-mile section through the Sierras I originally missed. But I’m also back to document the trail and what the experts and hikers on it can tell us about nature, humanity and the changing world we can see from the footpath. And I’m lugging 45 pounds of photography and writing equipment in my pack so I can share what I see.

An Audacious Idea

The day before I planned to start hiking, I stopped by the Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) headquarters in Sacramento, California, to learn about the nonprofit organization behind the PCT’s maintenance, management and marketing.

Chris Rylee, the PCTA’s director of communications, greeted me outside the group’s premises, a glamorous office building replete with mirrored bay windows and a fancy water fountain. We scurried inside to dodge the record-breaking heat, a portent of the days to come. Inside, the post that once marked the official southern end of the trail filled a corner by the door. Canvas prints of breathtaking hiker submissions to the PCTA’s annual photo contest decorated the cubicles and office spaces.

I took it all in while trying to reconcile Rylee’s name and southern drawl with his tan skin, colorful tattoos and island vibes. “I’m a trans-racial adoptee,” Rylee later explained. “I have loving, amazing white parents, but I was raised in West Texas in a town of 9,000 people where I was the only Asian person.”

After a quick tour of the space, including stops to see the official PCT completion medal press and an impressively stocked, hungry-hiker-friendly office pantry, we sat down to discuss the PCT’s creation, conservation and the role of climate change in its coming plans. “This didn’t just come out of nowhere,” said Rylee, describing the trail’s beginnings. “This took some audacity. There was some boldness, some vision, to be like, ‘You know what, why don’t we create something continuously from border to border, from north to south, south to north.’”

Rylee then walked me through all the notable visionaries without whom the PCT would never have come to be. Catherine Montgomery, a founding faculty member of what would become Western Washington University who was inspired by the Appalachian Trail stretching from Georgia to Maine to suggest the creation of a similar path along the crest of the states of the Pacific U.S. Clinton C. Clarke, a wealthy Californian who tirelessly advocated for the trail, drew out its entire route and self-financed thousands of books, maps and pamphlets about it. Key cameos came from the YMCA, Boy Scouts, famed California landscape photographer Ansel Adams and finally President Lyndon Johnson and the National Trail Systems Act in 1968. “These audacious, ridiculous people were like, ‘Let’s connect all of them,’” said Rylee, referencing the numerous fragmented hiking trails strewn across the mountains of the Pacific states prior to the unifying efforts for the PCT.

Over time, the PCT has slowly but surely drawn the public eye, and its legs. The strict quota of 50 thru-hiking permits a day issued by the PCTA on behalf of the U.S. Forest Service are almost always claimed mere minutes after the application portal opens, resulting in close to 8,000 registered hikers on trail each year, with many thousands more enjoying the trail on shorter, saner jaunts.

However, the original vision of a singular, straightforward hike from end to end has been complicated by increasing climate anomalies over the thousands of miles of trail.

Forest’s Fever Forces a Flip Flop

Apropos of that, my plans to hike the very next day were upturned by the blistering California heat wave, which prompted me to set off 100 miles south and several thousand feet higher than where I had first planned to start, seeking cooler conditions. All life on trail—including “dirtbag hikers,” as long-distance trekkers affectionately call themselves—are constantly in search of such “climate refugia” in the warming world. I plan to hitch a ride back up to my original starting point a week later to finish what I’d missed, when I hope that section of the trail is less feverish.

The “flip-flop,” as this discontinuous form of thru-hiking is called, is increasingly common and necessary to avoid hazards and unexpectedly wild weather conditions on the PCT. Such tactics are slowly gaining acceptance, even among long-distance hiking purists.

“The flip-flop is absolutely part of the modern way to navigate the trail,” said Rylee. “The ‘true thru’ in years like this year and a few years ago—the West Coast with all these wildfires is just not the place for it. And with the rest of climate change bringing record amounts of ice and snow,” more disjoined hikes will be increasingly common. Indeed, skipping a section of the trail was exactly what I also had to do in 2019 to have had any chance of reaching Canada.

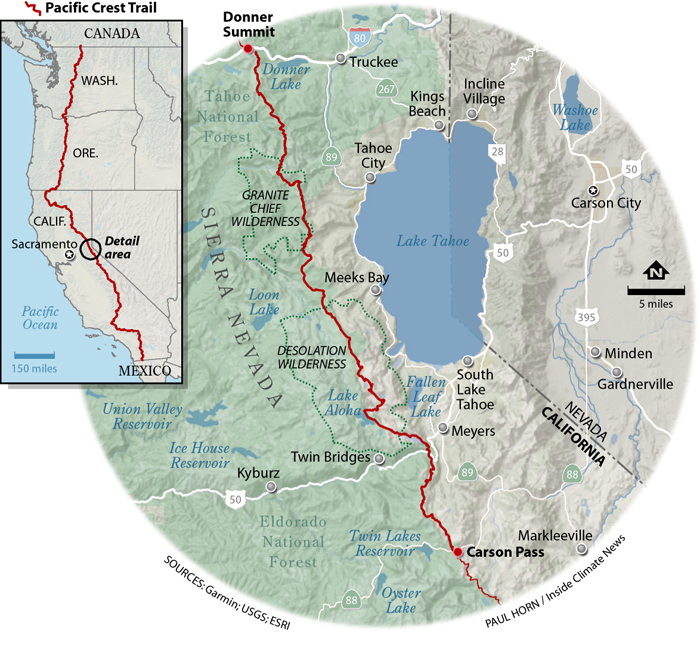

On Day 1 of my opening 80-mile hike southbound from Donner Summit to Carson Pass, I was already experiencing what Rylee described as nature’s allure. “All I can hear is the pounding of my heart in my chest. It’s purely sensation,” he told me the day before. “One foot in front of the other or I’m going to fall down the mountain. I’m thirsty, I’m hungry, and then you hit that vista and all that kind of burns away. Then there’s this moment of something bigger than myself.”

When I wasn’t gawking at the view or gasping for air, I was making good mileage through several of the national forests and wilderness areas that the PCT crosses. Tahoe National Forest, Granite Chief Wilderness, Eldorado National Forest, Desolation Wilderness, Lake Tahoe Basin.

“The PCT is ridge to ridge. It’s peak to peak,” said Rylee. “Humans didn’t travel that because it was convenient. They traveled that because it was something to see, something to do, something to push themselves.” The historic long-distance pathways that settled America, such as the Oregon Trail, sought out the paths of least resistance. But, as Rylee pointed out, the trails blazed as part of the nation’s conservation movement, including the PCT and the Appalachian Trail, followed the paths of greatest resistance.

I entered Desolation Wilderness on Day 2 and on the night of Day 3, camped by the massive boulders surrounding Fontanillis Lake (my new favorite pool). Unfortunately, these did absolutely nothing to temper the windstorm that laid siege to my ultralight backpacking tent that night. It would surely have flown down to the next lake a mile away had it not been for my battered body within it desperately anchoring it in place. The serene sunrise reflecting over the lake outlet on my way out that morning belied the pandemonium of just a few hours earlier and almost made up for the trouble.

The feeling of the wilderness is punctuated, and accentuated, by moments when the illusion of being in the wild breaks. Fallen logs sawed in half to make way for the trail, for instance, underscored the many others that I had to climb over or find a way around. The feeling of hiking in a desolate wilderness evaporated with the turning of a corner to see blue-jeaned day hikers and smell the overpowering aroma of detergent when the path snaked back toward civilization.

These are the very types of people that the PCTA would love to see out on the trail more, enjoying and enriched by nature. “There are 17 million that live within an hour of the PCT,” Rylee told me. “We’re doing more messaging around day hike, weekend hike, week-long, short sections,” as these demographics have the potential to vastly outnumber the thru-hikers on trail.

There are few pockets of true wilderness left in California, and the PCT crosses none of the most remote places left anymore. In fact the trail, which has grown much more popular in just the last decade, has contributed to the declining feel of remoteness in areas that it travels through. Heading south, against the main flow of hiking traffic, I guessed I passed between 20 to 30 northbound long-distance hikers each day, most of them planning to walk all the way to Canada and praying for safe passage.

Requests for divine protection make some sense, considering that in California alone, the Donomore, Gold Complex, Royal, Shelly, SQF Lightning, Vista and White fires have all contributed to ongoing trail alerts or closures this year.

On trail, there aren’t any of the training wheels or bumper rails that we’ve come to rely on in the civilized world. Record high temperatures are hard to comprehend from a climate-controlled work desk. Persistent drought doesn’t feel like a problem when you aren’t thirsty. Just as some communities feel greater climate impacts than others, the PCT, at the intersection between humans and nature, presents an unfiltered glimpse into what the world is like without any engineered creature comforts.

Exposed to the elements in my head wrap and visor during the day and in my little yellow tent at night, I feel like a weather stick for the tough times to come.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,