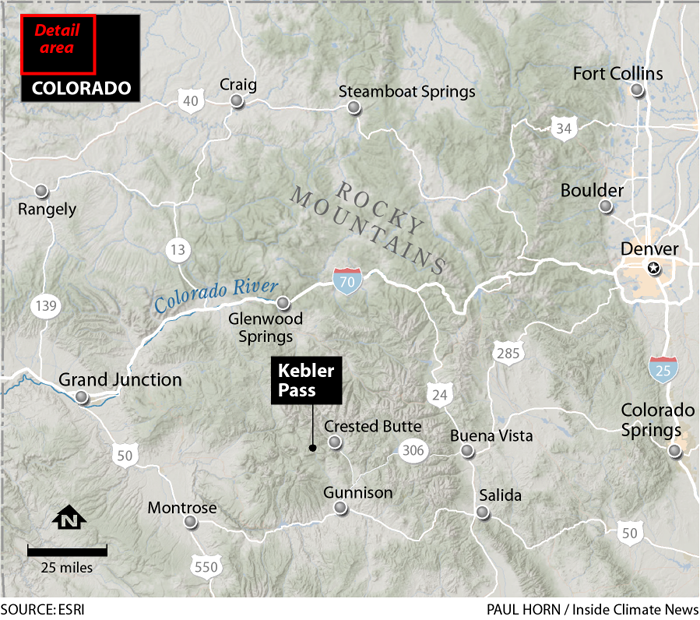

On the shoulder of Kebler Pass, about seven miles west of Crested Butte, a giant lounges in the Colorado high country.

The Kebler Pass aspen stand covers the equivalent of just over 100 football fields, with over 47,000 aspen trees, populus tremuloides, connected by a single, subterranean root system called a rhizome. The trees are all clones of one another, have similar branching patterns and turn a brilliant gold in unison when fall settles in on the high peaks of the Sawatch Range, creating an enormous, glowing swatch that outshines the surrounding forest’s other muted colors.

“It’s absolutely spectacular,” said Will Roush, the executive director of Wilderness Workshop, a Carbondale, Colorado-based environmental advocacy organization. “There’s no prettier place to be in the fall when they’re turning gold, thousands of trees at a time.”

Aspen stands are Roush’s favorite forest to spend time in—their magnitude and ecological diversity serve as a motivating reminder of his work. “Being in a grove of pure aspens speaks to my soul.”

Roush has spent a lot of time in aspen stands, both for personal fulfillment and as part of his work as an environmental organizer. He has organized community events that involve camping in aspen stands to protest oil and gas development. “It was really grounding to immerse ourselves in that landscape before working hard to give it a voice,” he said.

Kebler’s trees are thought to be between 100 and 150 years old, meaning the oldest shoots, called “suckers,” were breaking through the ground in the twilight of the Civil War.

This aspen stand competes for the title of Earth’s largest organism. While the Pando aspen stand in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest unofficially holds that honor, without an incredibly involved survey, it’s impossible to determine which stand is truly the largest.

But humans are drawn to the enormous, and the scale of the Kebler stand has activated a diverse, and occasionally unlikely coalition of people to protect it in a grassroots strategy that is increasingly key to conservation in the West.

Aspens are relatively delicate trees. Their thin bark makes them susceptible to disease and parasites, and the U.S. Forest Service has reported an uptick in a phenomenon called Sudden Aspen Decline, with the apt acronym SAD. Warmer temperatures associated with climate change leave the trees stressed and vulnerable, and drought compounds pressures of heat and insects. According to the USFS, Colorado has seen widespread, severe and rapid dying of 13 percent of its aspen trees.

Until recently, the Kebler aspen stand had to contend with another major threat: resource extraction.

But on April 3, the Biden-Harris administration announced 20 years of protections for the Thompson Divide, an area of mid-elevation Colorado backcountry that straddles 250,000 acres of public land between the Roaring Fork and North Fork valleys. Its tendrils reach from above Glenwood Springs through the ski runs on Sunlight Mountain and west above Carbondale, a small town in Aspen’s orbit. It’s sought-after territory for deer and elk hunters and prized as a swath of roadless side-country. The Divide, as locals affectionately call it, doesn’t just contain some of the valley’s most beloved hidden recreational gems, it is also home to endangered species like the lynx.

While the federal government delivered the protections, they were largely achieved by a community effort that brought together seemingly disparate groups—cowboys and conservationists alike—much like the myriad trunks of the aspen grove. In an age of political gridlock in which conservationists increasingly see efforts to enact environmental legislation as lost causes with public lands protections treated as political footballs or tacked onto bills that don’t make it out of committee, such grassroots organizing is proving to be one of their most effective tools.

“This type of collaboration can provide a refreshing contrast to a polarized political environment,” said Roush. “It’s a powerful statement. Allowing a community to speak up for a place and the range and diversity of voices is an added validator.”

‘Strange Bedfellows’ Unite to Save a Sleeping Giant

In 2012, a self-described “rag-tag” group of ranchers, business owners, mountain bikers, snowmobilers and environmentalists met in Carbondale. The group would become known as the Thompson Divide Coalition or TDC.

“It was formed as a group of strange bedfellows,” said Zane Kessler, the founding executive director of the TDC. “We had these seemingly divergent interests coming together because of their shared interest in protecting the Divide long term.”

In the early 2000s, the administration of President George W. Bush aggressively expanded oil and gas production on public lands. At that time, the Department of the Interior ceased conducting environmental reviews and accepting public comments for new fossil fuel wells and projects on existing permits.

An energy bill passed in 2005 created new “Categorical exclusions” under the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that allowed the drilling of new wells without first conducting environmental studies or soliciting public feedback. About 80 oil and gas leases were issued on the Thompson Divide, and dozens more were issued in adjacent land parcels. While local sentiment was largely opposed to the development, the coalition was initially focused on giving a voice to the community that felt they had been left out of decision-making.

“We started bringing elected officials, opinion leaders and decision-makers to the Thompson,” said Kessler. “It is such a rugged terrain of mostly roadless area that is pretty hard to access for most folks. We took them out on horses or flew them in a six-seater, single prop plane.”

From the air, or a saddle, people could appreciate the scale of the landscape and the giant aspen stand, in particular.

Sloan Shoemaker, who served as executive director of Wilderness Workshop from 1997 to 2018, was instrumental in forming the TDC.

“We knew that we needed to get a coalition of people together to make this happen,” said Shoemaker. “Some mountain bike folks. Some snowmobilers, even though they were slow to get on board.”

Just like an aspen stand spreads its roots underground, the unseen work of grassroots organizations began to take hold in the community. What had started as a single stand of trees soon spread to cover an entire slope, then eventually colonized most of a sprawling mountain pass.

“We just kept reaching out,” said Shoemaker. “And slowly, we were able to bring more people in.”

While some in the TDC were focused on helping lawmakers experience the landscape firsthand, bringing ranchers and farmers to the table was just as instrumental in pushing the movement forward.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe North Thompson Cattlemen’s Association, led by farmer Bill Fales, captured attention with a tractor parade down Carbondale’s main street, signaling a key endorsement from the agricultural community.

“I get goosebumps just thinking about it,” said Shoemaker. “This is exactly what we needed to capture the attention of our congressional delegation and the larger world.”

Grassroots Efforts Spread across the West

That awe and enthusiasm has spread to other conservation efforts across the Mountain West. In 2013, a coalition of ranchers, anglers, hunters, hikers and environmentalists won protections for the Rocky Mountain Front in Montana, an area connecting the state’s jagged granite peaks to its softer ambling prairies to provide habitat to a vast range of biodiversity. The diverse array of stakeholders, including private landowners and conservationists, were essential in protecting the patchwork of public and private land that connected vulnerable prairie lands and mountainous grizzly habitat.

New Mexico’s Valle Vidal, too, prompted enormous public outcry following a USFS petition to lease 40,000 acres to a company for methane production. The hunters and hikers who enjoyed the high desert ecosystem joined with environmentalists in an unlikely partnership and ultimately pressured Congress to adopt legislation prohibiting mineral development in the Valle.

In Wyoming, grassroots efforts organized by Keep It Public Wyoming were able to push back against land transfer bills that would hand federal lands to the state. That coalition galvanized a group of stakeholders so diverse, its rallies, many of which drew up to 500 attendees, were described as “camo next to tie-dye.”

Even in an era of increasing political polarization, public lands are a popular issue across the West and can unite diverse interest groups in a way that few issues do.

“It’s not a red versus blue issue,” said Fales, the farmer who helped found the TDC. “To have clean air, to have clean water. Everybody wants that.”

According to Colorado College’s annual Conservation in the West Poll, 85 percent of voters, including 74 percent of Republicans, 87 percent of independents and 96 percent of Democrats, say issues involving clean water, air, wildlife and public lands are important when voting.

The grassroots organization of the TDC was instrumental in supporting the legal work, and applying pressure on agencies, according to Peter Hart, who served on the legal team for Wilderness Workshop and headed up its effort to retract oil and gas leases on the Thompson Divide.

“We really worked hand in glove,” said Hart. “People were showing up at public meetings like never before. It was standing room only. People were showing to just slam the agency about how this area needed to be protected.”

“It’s not a red versus blue issue. To have clean air, to have clean water. Everybody wants that.”

And it worked. The public eventually submitted more than 65,000 comments during an open review period, forcing the USFS to cancel leases and pressure the Bureau of Land Management to do the same.

“Similar to an aspen stand, these community efforts were huge in scale,” said Roush. “You have hundreds, thousands even, of people coming together for a shared interest in protecting public lands.”

“We were fighting tooth and nail at every opportunity,” said Hart. “But it was the community that gave this effort the profile and volume that we really needed to flip the script.”

While aspen are susceptible to threats like heat and insects, they are hearty in other ways. They are sun-loving trees that can thrive even when human activity like logging disrupts other tree systems. They depend on fire to burn back bigger trees, allowing the aspens to spread their roots and spring up on sunnier slopes.

Since aspen reproduce from their root systems rather than by spreading seeds, even if a stem dies beneath the soil, the roots can send out fresh suckers to begin the cycle of tree regeneration again. An aspen root is relilient, with multiple suckers diverging from the system to see which will survive long enough to take hold over the seasons.

Similarly, grassroots conservation work takes years. It took 20 years of organizing and effort for the TDC to win 20 years of protection. Organizers hope this will be enough time to pass additional legislation, like the Colorado Outdoor Recreation and Economy, or CORE Act, that would bundle the Divide with other areas in Colorado for more lasting protections.

While major legislation, like the CORE Act, is a gold standard for lasting protections, the future of many bills hangs in the balance with November’s elections. But even where traditional politicking has failed, diverse grassroots organizations have succeeded in protecting land from Montana across Wyoming’s plains, Colorado’s high country and New Mexico’s desert. Many in the conservation movement see this as a blueprint for how environmental protection efforts will succeed in the future, regardless of the party controlling the White House or Congress.

“We’ve seen agency policy change due to the work that we’ve done on Thompson,” said Hart. “I don’t think those changes would have happened had it not been for the work of local communities and concerned citizens in places like the Thompson Divide.”

The aspen trees on Kebler Pass and beyond continue to serve as a potent reminder of the work yet to be done for organizers like Roush and also serve as a source of inspiration for what has already been achieved.

“These places inspire these coalitions,” said Roush. “It’s amazing to think about the coalitions themselves and that they represent this broad spectrum of people, and what brings people together is the place itself. That speaks to the power of natural landscapes and public lands and how these forests make people willing to set aside differences.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,