ODANAH, Wis.—“This is the last turn and the end of the fourth hill of life, when Bad River, as a spirit, transforms into something other, something extraordinary,” Mike Wiggins said as he rounded a final bend in one of the largest and most pristine wetlands on the shores of Lake Superior, one of the biggest freshwater lakes in the world.

It’s “similar to our spiritual journey off this planet into something other and extraordinary.”

From the driver’s seat of his small fishing boat, Wiggins, the former chairman of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, contemplated his surroundings with awe as a bald eagle soared overhead.

Beds of wild rice, a key food source and cultural pillar of the Bad River tribe, danced in his wake, glinting under the afternoon sun and nearly ready for harvest.

“This is a power place,” he said as he blasted Unbound, a recently released album by musicians including fellow Bad River tribal member Dylan Jennings. “It’s just no place for an oil pipeline.”

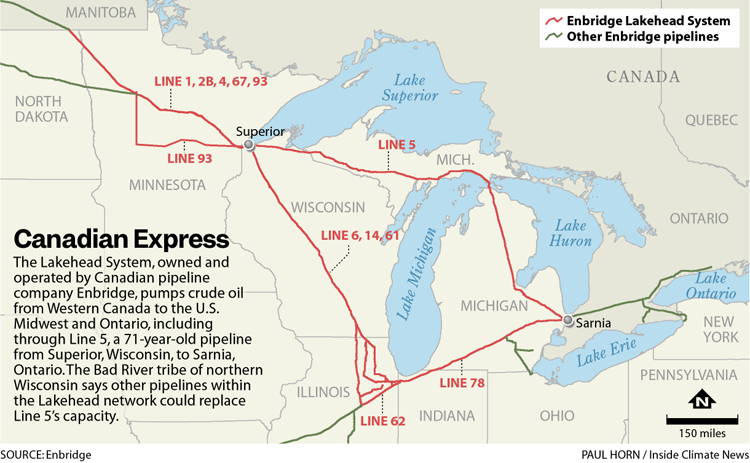

It has one, though. Seventy-one years ago, Lakehead Pipeline, a predecessor to Canadian pipeline company Enbridge, commissioned the construction of Line 5, a 30-inch diameter crude oil pipeline that transports up to 540,000 barrels of hydrocarbons per day from Superior, Wisconsin, to Sarnia, Ontario. The 645-mile line is part of a network that originates more than a thousand miles to the northwest in the oil fields of Alberta and, in the case of Line 5, ends back in Canada. It includes a 12-mile stretch that bisects the Bad River reservation, which is heavily forested with river crossings and large swaths of wetlands.

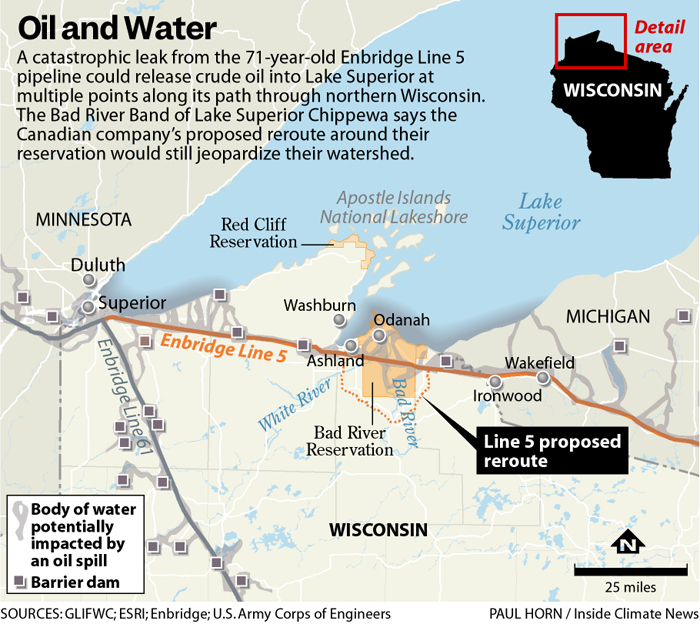

Any spill from the pipeline would drain into the Bad River and Kakagon Sloughs, where Wiggins fished. Known as the “Everglades of the North,” the area is protected under an international environmental agreement as well as multiple treaties between the U.S. and the Chippewa people, also known as the Ojibwe.

The path through the reservation was originally approved by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, more than a dozen easements granted to the pipeline, which was completed in 1953, have since expired.

In 2017, the Bad River tribal council voted unanimously not to renew them. Two years later, the tribe sued to have the pipeline removed from the reservation. The ongoing “David vs. Goliath” legal battle was chronicled in Bad River, a recent documentary.

In 2023, Judge William Conley of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin ruled in favor of the tribe and gave Enbridge three years to stop pumping oil through the reservation. The pipeline company has appealed the ruling.

One area of primary concern for the tribe is “the meander,” a naturally occurring bend in the Bad River that is slowly eroding a riverbank near Line 5’s route.

In 1963, a decade after installation, the pipe was 320 feet from the river’s edge. By 2015, the distance had narrowed to approximately 80 feet. Recent storms, including a severe flood that ravaged the area in 2016, have reduced the distance to within 11 feet.

“It’s an accident waiting to happen,” Robert Blanchard, chairman of the Bad River tribe, said of the meander. Blanchard, who will turn 70 later this month, is one year younger than Line 5.

“I know how I feel when I wake up in the morning and my bones creak and I’ve got a little sore here and there,” he said. “You can imagine what a piece of metal is like laying in the ground. You can’t tell me that it’s like it was when it was first put in. It deteriorates, just like I am.”

The soft-spoken Blanchard, who goes by the nickname Buzz, considered the consequences of that deterioration from his desk at the Chief Blackbird Center in New Odanah on a rainy summer afternoon. New Odanah, or new village, a settlement of approximately 500 people, was built in the early 1960s after a flood took out much of Odanah, the reservation’s original village. It was located on a floodplain of the Bad River several miles to the west.

Researchers who study floods view the move to New Odanah as an early and successful example of managed retreat: communities inundated by severe rainstorms or rising seas, events that are increasingly induced by climate change, moving to higher ground. However, some tribal members say the move from the river, driven by federally funded housing, was yet another forced relocation.

Blanchard recalls how as a young man he and a friend floated along “Mashkiiziibii,” the Medicine River, or Bad River as it is officially known, from far upstream of the meander to the river’s end at Lake Superior. He continues to collect medicinal plants from the river and nearby wetlands, just as his grandfather taught him to do.

Author, journalist and former Bad River spokesman Mark Anthony Rolo once described the reservation as “small, with a modest casino, and always on the verge of going bankrupt.” Rolo, who died in 2020, made that observation nearly a decade ago when his tribe was fighting another multinational corporation, Cline Group, which sought to blast one of the largest open pit iron-ore mines in the world near the headwaters of the Bad River.

His family’s homelands, Rolo wrote, “could never be for sale.” In 2015, Cline’s Gogebic Taconite subsidiary withdrew its application for the proposed mine.

The tribe’s response to a new threat remains the same. In March, Enbridge offered the tribal nation $80 million—far more than the $5.1 million awarded by the federal court the year before—if it would drop its ongoing lawsuit against the company.

“Our homeland, our treaty rights, and way of life are not for sale,” Blanchard wrote in response to the company’s offer.

Sitting at his desk, the chairman described photos he saw of the Kalamazoo River in Michigan after Line 6B, another Enbridge pipeline, ruptured in 2010. The spill released more than 1 million gallons of crude oil, making it one of the largest inland oil spills in U.S. history.

“Can you imagine what it would be like if that river full of black fell into Lake Superior?” he said. “We don’t want that there.”

Enbridge spokeswoman Juli Kellner dismissed concerns of a potential spill.

“Safety is the very foundation of our business at Enbridge, and prevention is the primary focus of our pipeline safety strategy,” Kellner said in a written response to Inside Climate News. “In addition to our industry leading design and construction standards, every day, our inline pipeline inspection and monitoring programs ensure multiple layers of safety.”

‘Substantial and Unacceptable Adverse Impacts’

In April, the U.S. Department of Justice weighed in on Enbridge’s appeal of the Bad River Line 5 lawsuit. The agency reiterated that the Canadian company has been “consciously trespassing on tribal land” and characterized the $5.1 million award to the tribe as a “paltry amount” for Enbridge’s “ill-gotten gains.”

However, the Justice Department gave credence to Enbridge’s argument that a 1977 pipeline treaty between the U.S. and Canada, which ensures the uninterrupted transmission of hydrocarbons by pipeline between the two countries, must be honored.

A ruling on the case by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals is anticipated in the coming months. Meanwhile, Enbridge is seeking to reroute Line 5 around the Bad River reservation with a new, 41-mile section of pipe that would skirt just south of the reservation.

The reroute, under consideration by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, would pass through the same Bad River watershed as the existing pipeline, and the tribe opposes it.

“It still can have very significant water quality impacts to the reservation,” Naomi Tillison, the tribe’s natural resources director, said while standing before a map of the proposed reroute down the hall from Blanchard’s office.

“I think there’s other options,” Blanchard said, noting that other pipelines in Enbridge’s “Lakehead System” could transport oil from Superior to Sarnia. One such pipeline is Line 78, a pipeline from Pontiac, Illinois, to Sarnia, Ontario, that was completed in 2015 as a replacement to Line 6B after the Kalamazoo River spill.

“They should have gone through Canada in the first place instead of bringing it down to our reservation,” Blanchard said of the decision in the 1950s to have the pipeline pass through Wisconsin and Michigan before re-entering Canada in Ontario.

Enbridge’s Kellner said the company has “no viable alternatives for transporting a substantial amount of the Line 5 volumes to the Upper Midwest and Canada as demand for petroleum and petroleum products remains high, and pipelines in the region are operating at or near capacity.”

“Shutting down Line 5 would cause an immediate shortage, and resulting higher prices, in the transportation fuels and other petroleum products refined in the region,” she added.

However, written testimony provided by Neil Earnest, a consultant hired by Enbridge and submitted in federal court in January 2022, concluded if Line 5 were shut down, gasoline prices would increase by just half a penny per gallon in Michigan and Wisconsin.

Kellner said that Line 5 is unique in that it transports both crude oil and natural gas liquids, which are refined into propane.

“Line 78 is not a viable option as it is not able to transport natural gas liquids,” Kellner said. “In addition, the line is substantially full.”

But a 2021 report published by Environmental Defense, an environmental organization based in Ottawa, concluded that gas produced in Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia could provide an alternate source of natural gas liquids for refineries in Sarnia.

“If Line 5 was shut down, the market would adjust,” Tillison said. “We think [the] Army Corps should be taking a harder look at alternatives.”

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials voiced concerns about the proposed reroute in written comments submitted to the Army Corps in a pair of letters in spring of 2022.

Tera Fong with EPA’s water division in the upper Midwest reminded the Army Corps in March 2022 that the Kakagon-Bad River Sloughs wetland complex is an aquatic resource of national importance and a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar treaty, designations that give it added protections.

“We believe the project, as currently proposed, ‘will result in substantial and unacceptable adverse impacts’ on the Bad River and the Kakagon-Bad River Sloughs wetland complex,” Debra Shore, an EPA regional administrator and Great Lakes National Program manager, wrote the following month.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe EPA did not respond to a request for comment on whether its concerns about the proposed reroute have been addressed.

The Army Corps said it continues to communicate with all interested parties, including the EPA, to address issues raised about the permit application.

“We are evaluating all methods to avoid and minimize adverse impacts associated with the proposed discharges of dredged and/or fill material in waters of the U.S., including wetlands, to the maximum extent practicable,” Bill Sande, a project manager in the agency’s regulatory division, said in a written statement.

A March 2022 letter to the Army Corps by then-chairman Wiggins noted that the Bad River tribe retains rights to hunt, fish and gather on the reservation, and in surrounding territories ceded to the U.S. government, through treaties signed in 1837, 1842 and 1854.

Ed Leoso, hatchery foreman for the Bad River tribe, said an oil spill anywhere in the Bad River watershed would jeopardize all those rights.

“It would be catastrophic,” Leoso said, standing near the boat launch of the tribe’s fish hatchery, which stocks millions of walleye into nearby lakes and streams each year. “It would pretty much destroy the river.”

Leoso said oil accumulating on the river bottom would be particularly harmful for wild rice.

“Once that oil accumulates on the bottom—you know, there’s seed down there—who knows when that’ll come back up again, if ever,” he said.

“That’s our main food source,” he added, looking out on the wetlands. “Everybody’s going to be going down here in a couple weeks to harvest rice.”

The Army Corps is currently accepting public comments on the proposed reroute. The tribe plans to submit written testimony on the proposal before the comment period ends on Aug. 30.

Enbridge’s Kellner said an oil spill anywhere along the proposed reroute would be “unlikely.” If such a spill were to occur, “there is no credible scenario where crude oil would reach Lake Superior from the relocated segment,” Kellner said. “In the one in 15 million chance there is a full-bore rupture on this segment, crude oil would not reach Lake Superior even after 48 hours with no emergency response at all.”

However, spill modeling commissioned by Enbridge for the proposed reroute notes that under an “extreme worst-case scenario,” more than a third of the oil would “remain on the surface or enter Lake Superior at the end of the 4-day simulation.”

As dusk fell over the Bad River, Wiggins stowed his fishing gear and prepared to make his way back upstream.

Before him, the waters of Lake Superior, famous for its shipwreck-inducing storms, were unusually calm, clear across Chequamegon Bay to Madeline Island, the spiritual center of the Ojibwe.

“They had come all the way from the Atlantic Ocean, searching for the place where food grows on the water,” Wiggins, now site director of the Madeline Island Museum, said of his ancestors’ travels to find manoomin, or wild rice. “This became the center.”

In less than a month, the August moon, known in Ojibwe as the “ricing moon” or “sturgeon moon,” would rise over these wetlands, one of Lake Superior’s last remaining strongholds for both wild rice and lake sturgeon. It would be a supermoon, one of the largest and brightest of the year. For now, however, the only light on the water came from the LCD display of the boat’s navigation system.

Making his way through the darkness, Wiggins continued to play Unbound from the boat’s speakers. The album, a blend of Powwow singing and electronic drums, offered songs of hope and defiance as well as plaintive prayers.

Few of the vocals were in English. Those that were seemed to hang over the water.

Take what you want from me

Don’t hurt those rivers and streams

This is our land

And she’s all we have

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,