Last year was already one for the climate record books, but a new report from the American Meteorological Society is adding to that already substantial list.

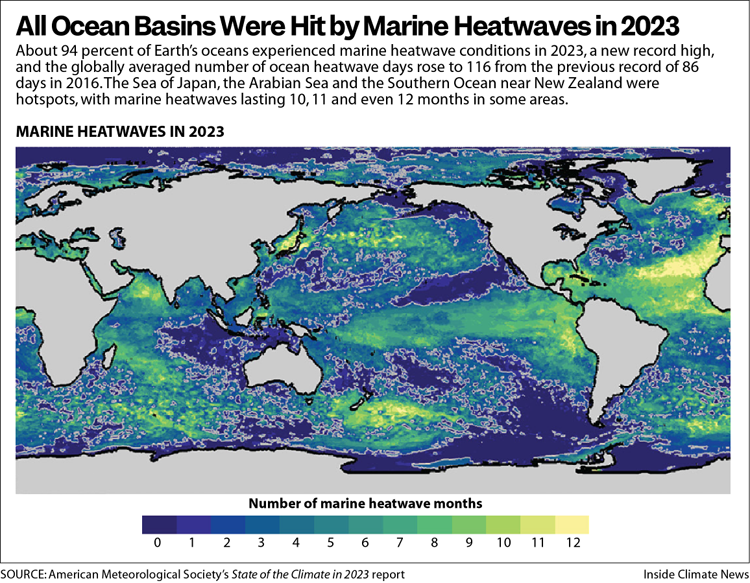

In 2023, Earth’s layers of heat-reflecting clouds dwindled to the lowest extent ever measured. About 94 percent of all ocean surfaces experienced a marine heatwave during that year. And, last July, a record-high 7.9 percent of land areas experienced severe drought, the report shows.

The root cause of the feverish symptoms is the continued buildup of heat-trapping pollution from burning fossil fuels, the report states, detailing the record-high concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide last year.

The State of the Climate in 2023 was published Wednesday as a supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. It was compiled by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information with contributions from scientists around the world, and includes extensive analysis of global climate conditions in a record-hot year that drove dangerous extremes around the planet.

Last year’s global ocean temperatures in particular stood out to many researchers because they were so far above previous records. The persistently high surface temperatures may mark a “step-change” of climate conditions, said Boyin Huang, a researcher with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who worked on the oceans section of the report.

The global average annual sea surface temperature anomaly was 0.13 degrees Celsius above the previous record set in 2016, a very large jump for the oceans, he said, adding that marine heatwaves were exceptionally widespread and persistent in many regions.

Ocean heatwave conditions stayed in place for at least 10 months of 2023 across vast reaches of the eastern tropical and North Atlantic Ocean, the Sea of Japan, the Arabian Sea, the Southern Ocean near New Zealand and the eastern tropical Pacific. And the globally averaged number of ocean heatwave days rose to 116 from the previous record of 86 days in 2016. At the other end of the scale, there were only 13 marine cold spell days, far below the previous record low of 37 days, set in 1982.

The ocean heat was so remarkable that Huang wrote a separate paper, published July 25 in Geophysical Research Letters, that adds “super-marine heatwaves” to the modern climate glossary, alongside terms like megafire and megadrought.

Huang said he and his co-authors didn’t take lightly the decision to use a new word, but felt it was needed to communicate the extreme level of ocean warming and the associated impacts in recent months. Ocean heat in 2023 wiped out remnant coral colonies in the Caribbean and other regions that were already severely damaged by previous ocean heatwaves, and also resulted in mass die-offs of fish, seabirds and marine mammals.

Co-author Xungang Yin, also a NOAA climate researcher, said the new super-marine heatwave category effectively describes the recent uncharted heat levels in oceans.

“Sometimes people classify marine heatwaves from category one to category four,” he said. “But a super-marine heatwave is above all that. It’s the highest we can get.”

Huang said the classification is important in the context of understanding impacts to ocean ecosystems because it means the temperature has never before been as high in a given area.

“So that means the impact to the ecosystem has never been so severe or serious,” potentially with unprecedented consequences, he said.

That scenario played out in the Caribbean last year, as coral reef researchers saw certain types of soft corals that hadn’t been damaged by previous heatwaves bleach and die. The ferocity and duration of the ocean heat in the western Atlantic surprised the scientists and overwhelmed the organisms, including small coral restoration projects where a better warning may have enabled scientists to take some protective actions.

The long-lasting marine heatwave in the tropical North Atlantic has also been a source of concern for scientists, who projected a very active hurricane season based in part on that warmth, the fuel that sustains tropical storms and can also help such storms intensify rapidly into major hurricanes.

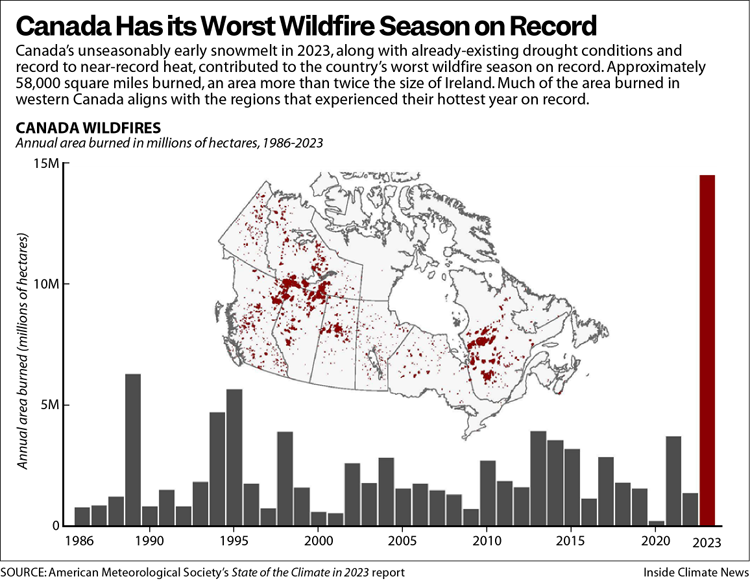

The report also highlighted the severe wildfire season in Canada, where almost 60,000 square miles of forest burned last year after the winter snowpack melted much earlier than in an average year. With pre-existing drought conditions, many forests were primed for fire.

“Much of the area burned in western Canada aligns with the regions that experienced their hottest year on record, as well as those that experienced prolonged drought conditions,” the report states, adding that more than 200,000 people were evacuated from fire-threatened zones, including all 20,0000 residents of Yellowknife. The smoke from the fires created public health hazards across parts of North America for weeks and even reached Western Europe.

Clouds are Still the Wild Card in the Climate System

As land and oceans heated to record highs last year, the skies above cleared, with 2023 as the least cloudy year on record since detailed measurements started in 1980.

“That means skies were clearer around the world than on average,” said Huang. As a result, clouds had their weakest cooling effect on record, because they reflected away to space the least amount of incoming energy from the sun. Research in 2021 suggested that changes in cloud coverage will amplify global warming in the decades ahead.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe report notes that, since 1980, clouds have decreased by more than a half percent per decade, increasing the likelihood of record minimum years like 2023, “when the lower-than-average cloudiness was distributed globally, with the Indian Ocean, Arctic, and Northern Hemisphere land being especially low in cloudiness,” the report noted.

Clouds are still a tricky part of the climate equation, said Michael Mann, director of the Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the new report.

“It’s not quite as simple as the report summary might make it sound,” he said, adding that clouds can both cool and heat the planet.

“The latter is particularly important in the case of high cirrus clouds, which have minimal reflective properties but substantial absorptive properties,” he said. “So one needs to know not just how cloud cover amount is changing, but what types of clouds are changing.”

The current scientific consensus is that clouds’ insulating effect on the Earth is stronger than the cooling from their reflecting solar radiation away from the planet, “so clouds are contributing to warming,” he said. That’s what most climate models capture, but because the models vary greatly in how they represent cloud radiative feedbacks, there is still a lot of uncertainty in this area, he added.

The sudden shifts in major global climate systems in 2023 has also left some scientists uncertain about the coming years.

The 2023 global temperature anomaly in general came “out of the blue,” Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, wrote in a March essay in Nature.

If the surge in temperatures continues beyond the summer, he wrote, “It could imply that a warming planet is already fundamentally altering how the climate system operates, much sooner than scientists had anticipated.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,